Isabella is part of the line up at this year's Hay Festival within the 'Green Hay Forum', sponsored by Triodos Bank.

Your book has been a big success and struck a chord with many people. What prompted you to write it?

We’ve been on a tremendous journey with our farm. I wanted to write the book because what we were discovering is so astonishing and hopeful. We’ve devoted the 3,500-acre Knepp Estate, just south of Horsham in Sussex, to a rather radical project aimed at nature conservation. The book offers a practical way of turning around some big issues, such as biodiversity and carbon loss, soil degradation and air and water pollution.

Where does your personal motivation and inspiration for the project come from?

It was a question of economics, to be honest. We inherited the farm in the 1980s and after 17 years of trying to farm intensively on our land – heavy Weald clay over a bedrock of limestone – we were left £1.5 million in debt. We realised intensive, modern agriculture was just not suited to this land and so we stopped. Once we were released from that blinkered mindset, we were able to think creatively and objectively about what we could do – working with the land rather than battling against it. It was then that we encountered this idea of ‘rewilding’.

Who were the important individuals and organisations that helped you on this journey?

Visionary Dutch ecologist, Frans Vera, first showed us that free-roaming herbivores can create habitats and stimulate biodiversity. In Europe, before human impact there would have been huge populations of animals shaping our landscape and ecology. Frans has been inspiring and is an open and honest person in himself. The Knepp project has of course been helped by many other wonderful people, most of which I have tried to recognise in the book and on our website.

In terms of our food and farming system in the UK, how do you feel rewilding fits in?

Rewilding could connect areas of nature together that would otherwise be left isolated. If we just have small, detached pockets of nature, they will die. We must create a better, joined up landscape and at Knepp we have shown that rewilding is a very quick and effective way of doing that.

We do produce food – organic, free-roaming pasture-fed meat – but that is incidental. We are really a nature restoration project and we’re not saying we’re an alternative to land for farming. That said, we have also learnt from the project that we must change the way most modern farming is working. Our soils are suffering, we cannot use so many chemicals and we need to reduce ploughing. Regenerative farming is the way forward.

Photo: Charlie Burrell

Photo: Charlie Burrell

Bluebells | Photo: Charlie Burrell

Photo: Charlie Burrell

Photo: Charlie Burrell

View of the castle from Knepp Lake | Photo: Charlie Burrell

How have you found public understanding of rewilding has developed in recent years?

When we started, rewilding was synonymous with re-introducing predator carnivores, such as wolves (partly due to the concept developing in the USA). The UK media picked up on this idea and it was understandable that in Britain we were nervous about it. But nowhere in that picture were herbivores. Now that people can visit Knepp and see for themselves what rewilding looks like, it’s not so threatening. We show you can do really exciting things even in a small area in a busy corner of South East England – just 16 miles from Gatwick Airport.

Now rewilding has thankfully become more a part of common parlance. People talk about it now on all sorts of levels – not just at landscape scale. We are rewilding our gardens, our window boxes and even ourselves!

There has been some high-profile negative publicity around international wilding projects, for example in the Netherlands and Germany. Is managed wilding truly the story of hope for people and planet?

This is often a misunderstanding about what is going on. For Europeans, it can be difficult to see the boom and bust cycles of nature, because we are used to densely populated and carefully managed landscapes. We feel nervous about taking our hands off the steering wheel and allowing natural processes to happen. Rewilding shows what nature can do. At Knepp, insect numbers have exploded and we have some of the rarest species in Britain – bees, dragonflies, dung beetles and so much more. Turtle doves, peregrine falcons and purple emperor butterflies are now breeding at Knepp and biodiversity has rocketed.

How have you financed Knepp Farm and the wilding conservation work you have been doing?

We currently receive Higher Level Stewardship funding - an agri-environment payment from Europe. Who knows what will happen post-Brexit but it looks like the thinking from government is moving in the right direction in terms of paying farmers not just for producing food, but actively restoring soils and protecting the environment too. The aim, for us, though, is to be self-sufficient and so we have developed income streams from our eco-tourism business Knepp Wildland Safaris, converted old agricultural buildings into office space and sell the annual harvest from our herds of organic, pasture-fed, free-roaming livestock.

The final chapter of Wilding culminates in a call for us to look again at the value of nature. What motivated you to finish on that note?

It feels like in the last few years people have really woken up to what is happening to our planet and we are looking at the world in a different way – in particular, how we manage our land and our behaviour. But the way that we have been considering conservation is not working. I appreciate the argument that ‘nature is valueless’, but this then means it doesn’t get considered when decisions are made, for example when building a road or conurbations.

When you put a value on nature it becomes part of the bank balance and then it is considered seriously, and you can see how working with nature is much more efficient in terms of finance and the economy. You can also drive systems where the polluter has to pay and immediately this makes a difference to how we farm and use the land. This enables us to consider the ‘true cost’ of our food.

Considering nature in its economic terms doesn’t mean that it loses any of its magic and mystery, but in practical terms it is important to consider it in the way we operate financially.

About Isabella Tree

Isabella Tree is an award-winning author and travel writer, and lives with her husband, the environmentalist Charlie Burrell, in the middle of a pioneering rewilding project in West Sussex. She is author of five non-fiction books.

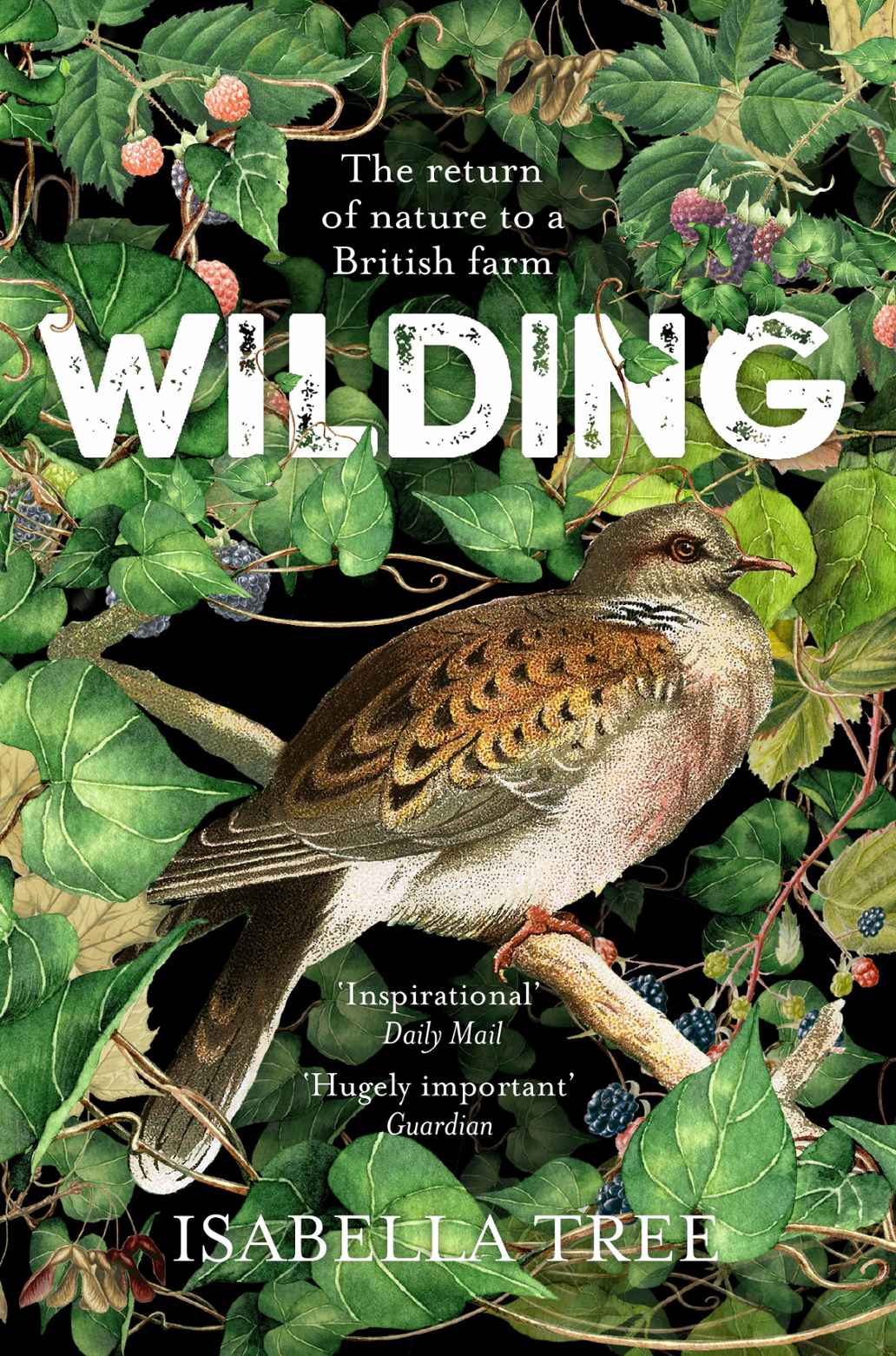

Wilding: The Return of Nature to a British Farm (Picador) is out now from all good bookshops.

How Triodos Bank supports natural capital

Triodos Bank has supported the organic, biodynamic and permaculture movements for many years. We lend to many organic food & farming businesses. Most recently, we have been exploring the potential for private sector investment to play a transformative role in restoring our natural capital through nature based solutions.

Thanks for joining the conversation.

We've sent you an email - click on the link to publish your post.